- [ANALYSIS] What ‘Gender equality today for a sustainable tomorrow’ Means for Women’s Political Representation in the Southern African Development Community? - October 16, 2022

- Can Civic Tech Flip the Script of Youth Participation in Elections in the SADC Region? - June 3, 2022

- Constitutional Review in Botswana: The Nexus between Cultural-Liberal Values and its Implications for Foreign Policy - January 18, 2022

At least six Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries are scheduled to hold elections within the next three years. Although elections represent a renewal or establishment of a social contract through voting, recent elections in southern Africa have not enjoyed support from the youth.

The African Union defines youth as individuals aged 15–35 years. The growing youth voter apathy and disinterest in electoral processes beg for innovative interventions that will inspire the former to become active stakeholders and participants in the region’s democratization project. Civic tech, in the form of online portals and social media platforms, has the potential to unlock such innovation.

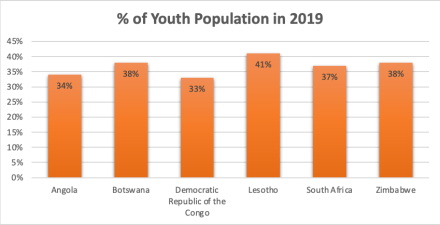

The general elections to be held in Angola and Lesotho in 2022, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zimbabwe in 2023, as well as Botswana and South Africa in 2024, require that the young people of these countries do not only engage in political activism -campaigns and protests- but also vote for political representatives or compete for political office. This is important since the youth constitute a significant proportion of the population of these nations (see Figure 1). Therefore, their votes, as well as their representation in political leadership positions will strengthen democracy.

LIMITATIONS TO YOUTH PARTICIPATION IN ELECTIONS IN THE SADC REGION

History documents the pivotal role African youth played in political changes across the continent in the twentieth century – including South Africa’s liberation struggle. However, their participation in elections has been waning over the years, a development that is attributed to a myriad of challenges this group experiences including high unemployment, marginalization, and under-representation in government institutions and political leadership spaces, as well as questionable elections.

In countries like Malawi and Mozambique, for example, recent elections were defined by gross irregularities that questioned the credibility of their outcomes. And, in the case of the former, the courts were forced to intervene and overturn the results. Even in a country like Botswana, which for decades has taken pride in being the beacon of African democracy, recent events point to worrying signs in the country’s democratization efforts. An unprecedented number of petitions brought against the 2019 elections, as well as concerns that a recent floor crossing legislation may have been designed to arrest the declining political fortunes of the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), highlight growing deficiencies in Botswana’s democracy. These occurrences evidently erode trust in electoral processes.

It is also worth noting that political discourses that take place on civic tech platforms like Facebook and Twitter – where most young people interact – serve to compound these challenges. Civic tech can thus be seen as a double-edged sword that exacerbates apathy and disinterest in young voters, but also has the potential to make political processes attractive and accessible to this constituency. The main challenge for the region’s pro-democracy advocates then is to come up with innovative measures to harness the democratic possibilities of civic tech while mitigating its adverse effects on youth involvement in the political process.

YOUTH PARTICIPATION IN ELECTIONS IN THE SADC REGION

There are several determinants of youth participation in elections in SADC.

Zimbabwe’s 2018 increase in youth voter turnout when compared to 2013, for example, could have been a response to legitimize Emmerson Mnangagwa’s rule after the 2017 coup. The euphoria of an anticipated new dawn, in the context of deteriorating socio-economic conditions, might have also catalyzed the high youth voter turnout. In Botswana, the Independent Electoral Commission cites increased youth participation in electoral cycles from 21% in 2004 to 41% in 2019, owing to increasing political engagements on social networking sites – Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, amongst others.

On the other hand, Lesotho and Angola experienced a decline of said voters in the 2017 general election; political dynamics contributed to youth disinterest in Lesotho’s case, while the latter had voter’s roll irregularities that relocated most voters to polling stations that they had not registered to vote at. This is likely to have inconvenienced and demoralized the youth, forcing many to stay away from the ballot box.

South Africa’s case of decreased youth voter turnout over the past six electoral cycles, reached a significant decline in 2019. As explained in a study by Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, this phenomenon was a result of the difficulty in mobilizing the youth population, low attachment or loyalty to political parties, negative economic evaluations, and low levels of political representatives’ responsiveness to the young electorate’s interests.

CIVIC TECH AS A CHANGE-MAKER IN COUNTRY-SPECIFIC INTERVENTIONS

The ongoing electoral cycles are confronted with new challenges pertaining to civic and voter education in the face of COVID-19. This is because minimized face-to-face civic and voter education activities in a bid to curb Covid-19 will only serve to perpetuate misinformation and youth voter apathy. The heightened distrust in government administrations and bureaucratic institutions to deliver on public goods, as well as rising corruption, amongst others, will also affect youth’s voter turnout in the upcoming elections.

As such, taking advantage of civic tech is important for all concerned stakeholders – i.e., governments, electoral management bodies (EMBs) political parties, civil society organizations (CSOs), the private sector, and the youth itself– to intensify election messaging, voter education, and dissemination of accurate, reliable information on electoral cycles. This will attemptedly counter misinformation while allowing political parties and election management bodes to reach a large proportion of the youth population.

For these civic tech initiatives to be successful, governments providing free data to their electorate will play a pivotal role. Although communication and technology infrastructure is available in most countries, not everyone can afford data allowances for a stable or high-quality connection. Therefore, providing data will afford the youth electorate access to civic tech tools. It cannot be emphasized enough what civic tech can achieve to boost youth confidence and trust in electoral processes. Mozambique, for example, is already using Citizen’s Eye and Txeka-lá, as well as the Votar Mozambique web platform and its mobile app to monitor polls in real time. This serves to curb electoral irregularities and enhances participation.

To address challenges limiting youth participation in elections in each of the selected SADC countries, civic tech interventions should be specific, as demonstrated in the table below:

Southern Africa’s communication and technology infrastructure can support civic tech initiatives to increase youth participation in elections. It is left for governments and other stakeholders to maximize available tools to influence and attract this demography to vote, as part of the measures to strengthen democracy in the region.

- What determines youth participation in the SADC region elections?

- Which civic tech tools would appeal to youth to enhance their participation?

- Who is responsible for youth participation in elections at a national level?

Suggested Readings

African Union (2019) State of the African Youth Report.

IEC (2019) ”South Africa:2019 National and Provincial Elections Report”

IJR (2016)”Youth Participation in Elections in Africa: An eight-country study.”

Pingback: The Current Political State of Zambia: Will Foreign Investments Be a Viable Decision? - The New Global Order