Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni pictured with a Citizens’ Income card. Source: Nicola Porro

Only 4 short years after Italy’s Five Star Movement created the Citizens’ Income program (known in Italy as Reddito di Cittadinanza), Italy’s first female Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni is phasing out the program. For those considered “employable”, they will only receive payments for the first 7 months of 2023 instead of 18 upon renewal as first promised when introduced by Italy’s coalition government. Those between the ages of 18-29 who have not completed their compulsory schooling, will only continue to receive payments if they attend training courses. Nuclear families with someone over the age of 60 years old, disabled family members, or minor dependents will continue to receive payments throughout the entirety of 2023. This fulfills Meloni’s campaign promise of ending the Citizens’ Income. She has clarified that it would have been impractical to end the program immediately, which explains why it will end in the summer. This permits the national government to have time to plan what comes next.

Ever since it has been introduced, the Citizens’ Income has been hotly contested, partly due to some regions of Italy benefitting from the program much more than others. In April of 2022, 65 percent of the 1,191,384 families who received the Citizens’ Income lived in Southern Italy. The population of Southern Italy only accounts for a third of the national population. 164,000 families in the province of Naples, with a population of slightly over 3 million, benefit from the program. This is over double the 81,000 families that benefit from the Citizens’ Income in the region of Lombardy, which has a population of 10 million (20 percent of the national population).

Meloni has chosen to limit who can receive the Citizens’ income because she argues that the program failed to achieve its objectives. It has not eliminated poverty or created jobs. Instead of continuing the program, she wants to focus more on offering training and courses in order to help Italians become part of the labor market, not rely on payments from the government. This is crucial as 70 percent of recipients have little education, making it challenging to find employment and not be reliant on the government. In the first two years of the program, the national government paid 19.83 billion euros in benefits. Considering the constantly growing national debt, however, the national government needs to cut expenses. High national debt and potential tax increases scare potential investors and foreign and domestic companies, creating a vicious cycle of low economic growth and high public debt that is difficult for the nation to end. In 2021, the National debt was equivalent to 2,678.1 billion euros (150,3% of the national GDP). In the European Union, only Greece has a higher national debt.

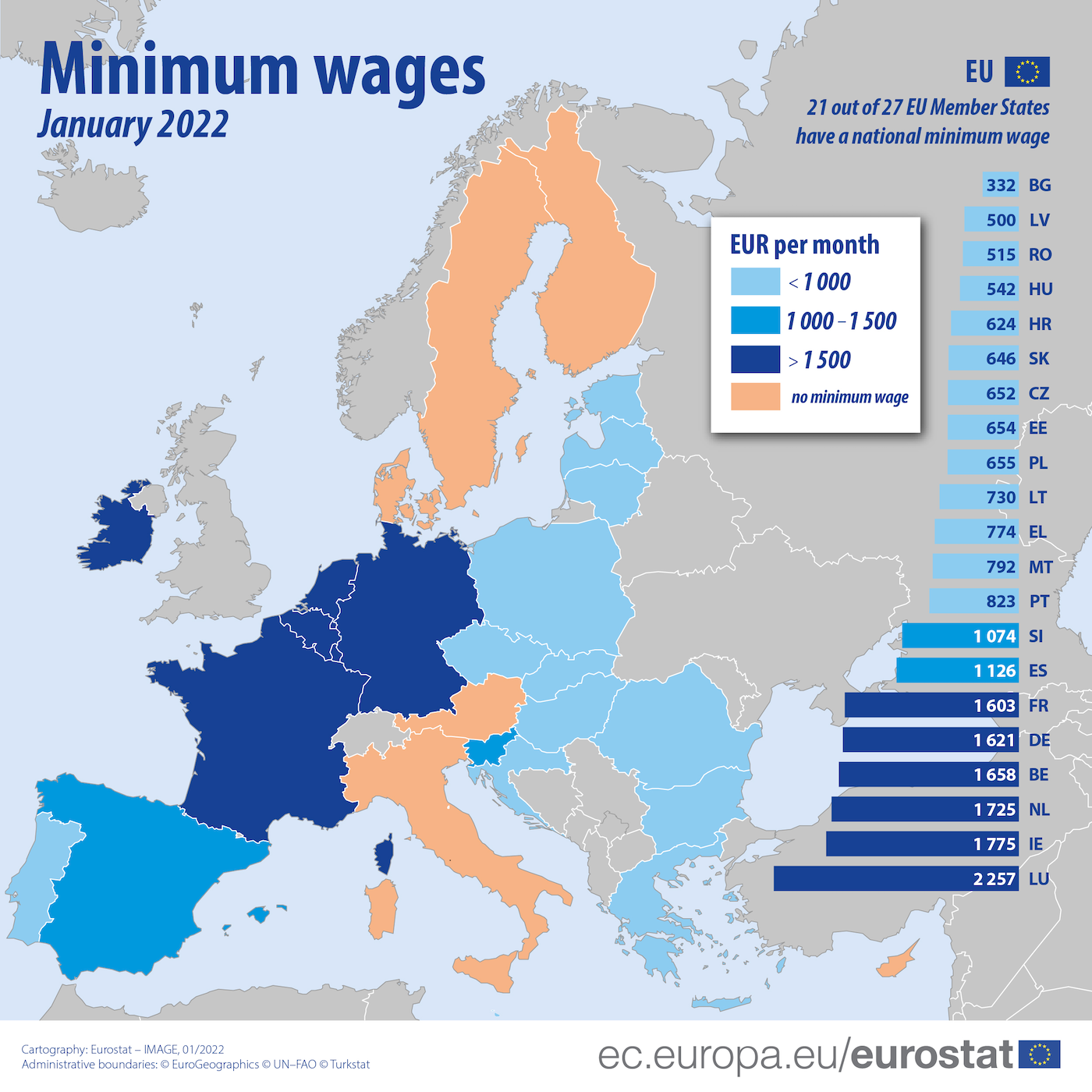

No Minimum Wage Law In Italy

One noticeable blind spot in Italy’s labor market is the absence of a minimum wage law. As other European Union member states such as Sweden and Denmark, Italy has workers protected by collective bargaining agreements. Sweden and Denmark are outspoken against a potential European Union minimum wage law as they perceive it as a threat to their current systems. The problem in Italy unlike Sweden and Denmark is, however, not all employees are covered by a minimum wage. Unless the collective bargaining agreements are extended to all employees, a minimum wage law would be beneficial in Italy in order to guarantee a minimum that workers must be paid and help eliminate a need for payments from the government.

Italy’s Shadow Economy

Italy has a flourishing shadow economy that preys on desperate workers. While Italy’s shadow economy is slowly shrinking as a share of Italy’s official economy, it still is a significant challenge for the nation. The shadow economy includes criminal activity unlikely to ever become legal such as the drug trade. There are also innocent people stuck in low-paying jobs due to employers wanting to cut costs. While 23 million Italians are regularly employed, it is estimated that 3 million work in the shadow economy, also known as irregular workers. It is estimated that 52.5 percent of domestic workers are irregular workers, equal to 781,900 workers. Other economic sectors with irregular workers include manufacturing, agriculture, hospitality, construction, and energy. The issue for these workers is that without an official contract, they can be fired with little notice. These workers also do not earn any pension benefits for the entire duration they work in the shadow economy, leaving them vulnerable in old age. This also leaves these workers more likely in need of government assistance.

Italy’s labor market woes will not be resolved overnight but Meloni remains dead set that the Citizens’ Income is not helping the matter. Her thought process of not eliminating the Citizens’ Income immediately, but instead phasing out the program in the summer, is better if the national government creates concrete solutions on how to end poverty, before the program officially ends. Sooner rather than later, the government must also decide how to address low wages either through a minimum wage law or by expanding collective bargaining to all employees in order to reform the labor market.

For More Information Please Read The Following: