On 28 March 2024, Fiji’s Prime Minister, Sitiveni Rabuka, announced that his government would be removing Chinese officers embedded within the nation’s police force, citing concerns about Beijing’s expanding presence in the South Pacific region. This controversial move shines a light on recent developments in Fiji-China relations, which have become increasingly strained since Rabuka’s Government took power following Fiji’s most recent general election in 2022.

Fiji’s gradual shift away from China and its growing rapprochement with the West not only mark the beginning of a new era in the nation’s dynamic foreign policy, but may also indicate a broader trend in the South Pacific, considering Fiji’s role as a geopolitical leader in the region.

This article details Fiji’s foreign policy, including its strategic navigation of geopolitical tensions, its long-term goal to balance between China and the West, and its mission to establish itself as an influential regional leader in the South Pacific.

Fijian Prime Minister shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the APEC Leaders’ Summit

Source: South China Morning Post

Fiji’s Traditional Foreign Policy and Post-Coup Realignment

Traditionally, Fiji’s trade, economic, and diplomatic relations were strongly linked to the West, particularly its Commonwealth neighbours, Australia and New Zealand, but also the United States and the European Union. On 5 December 2006, Fiji experienced its fourth coup since gaining independence in 1970, in which the military, led by Commodore Frank Bainimarama, ousted then-Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase and took control of the government.

While the new military government justified its actions as a necessary “coup to end all coups” that would move the country away from decades of corruption and ethnic tensions, the coup faced harsh condemnation internationally. Australia and New Zealand imposed extensive sanctions on Fiji’s defence and immigration sectors, the US cut $2.5 million in military aid to Fiji, and the Commonwealth suspended Fiji’s membership.

Fiji’s international reputation suffered further after its constitution was abolished in 2009, following a ruling from the Fiji Court of Appeal that declared the 2006 coup illegal and the subsequent military government illegitimate. As a result, Fiji was completely suspended from the Pacific Island Forum and the Commonwealth.

From 2009 onwards, Fiji would pivot its foreign policy away from its traditional Western partners and establish closer economic and diplomatic relations with China, recognising the nation’s rapid rise as a geopolitical and economic superpower wielding great influence over the Asia-Pacific region. This initiative, known as the ‘Look North‘ policy, was welcomed by China with great pleasure. China would rapidly increase its provision of development aid to and investment in Fiji in the years following 2009.

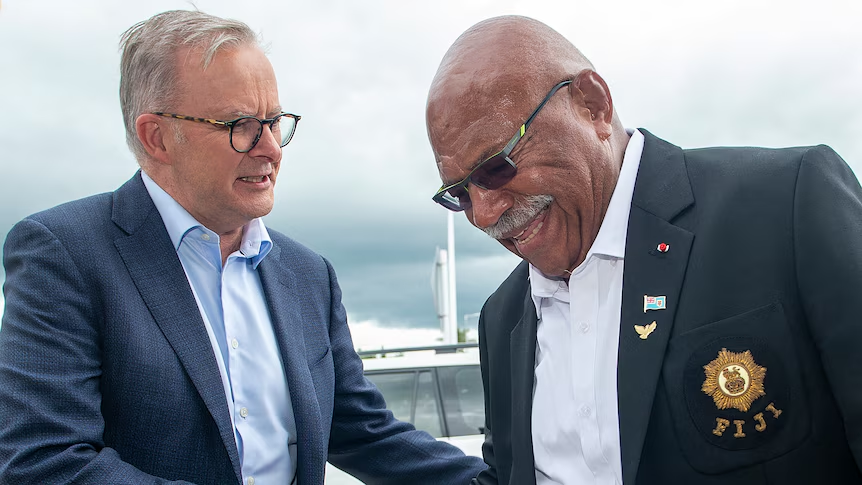

Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka meets with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in Nadi, Fiji

Source: ABC News

Fiji’s Rapprochement with the West as a Response to the Rise of China

Following the 2009 constitutional crisis and subsequent estrangement from its traditional Western partners, Fiji publicly committed to scheduling general elections for 2014. This move was formalised with the establishment of Fiji’s new constitution in 2013, drafted under Bainimarama’s Government with the aim of giving ethnic Indo-Fijians the same status as indigenous Fijians. This return to democratic norms and values mended Fiji’s relations with its traditional Western allies, with Australia and New Zealand restoring full diplomatic relations with Fiji, and the US resuming its security and financial assistance to the nation.

While this new arrangement initially appeared to be a win for Fiji’s foreign policy, allowing the nation to enjoy full diplomatic and economic relations with both China and the West, domestic and regional challenges presented Fiji with the dilemma to choose between them.

Fiji’s 2022 election was a pivotal one, with the narrow victory of a three-party coalition led by Sitiveni Rabuka resulting in the ousting of Frank Bainimarama, who had been in power since the 2006 coup. Under Rabuka, Fiji has taken a significantly more cautious stance towards China. While Rabuka has expressed that he is “more comfortable dealing with traditional friends” such as Australia, he has also acknowledged both China’s contribution of foreign aid to Fiji, stating that China’s Belt and Road Initiative aligns with Fiji’s development agenda.

Rabuka remains concerned about Beijing’s growing presence in the Pacific and its potential to undermine democracy in the region, warning that Fiji and the broader Pacific region do not want to be forced to choose between the US and China amidst their intensifying rivalry.

Since the 2022 election, Fiji’s relations with China have become increasingly strained. In January 2023, Rabuka terminated a memorandum of understanding between Fiji’s Police Force and China’s Ministry of Public Security, which had established joint police training activities between the two nations. Rabuka explained that due to fundamental differences between Fiji and China’s democratic and legal systems, Fiji would focus on collaborating with nations with similar systems, indicating closer security ties with the West, particularly Australia and New Zealand.

Former Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting

Source: Stratfor

Implications on the Pacific Region

So, what are the implications of Fiji’s shift in foreign policy for the rest of the Pacific region? Well, several other Pacific Island nations, as well as the broader international community, have expressed concern about China’s growing influence in the region. Both Japan and the US have taken a plethora of measures to contain Beijing’s influence in the Pacific, including new foreign aid packages, infrastructure funding for hospitals, roads, and bridges, and assistance for climate change mitigation and disaster relief.

While it is easy to assume that the Pacific Island nations can simply cut their political and economic ties with China, the matter of the fact is that most of the Pacific remains highly dependent on China for resources and development aid. Between 2006 and 2017, China provided nearly US$1.5 billion in foreign aid to the Pacific through a combination of grants and loans, becoming the region’s third-largest donor by 2017.

In fact, a growing number of Pacific Island nations have strengthened their diplomatic ties with China. Upon Taiwan’s election of Lai Ching-te earlier this year, whose government advocates for an independent Taiwan, Nauru transferred its diplomatic allegiance from Taipei to Beijing, and Tuvalu’s pro-Taiwan Prime Minister lost his seat in the nation’s general election.

To counter China’s growing influence in the Pacific region, it is in the best interests of Pacific Island nations to work together as an independent, unified bloc. Fiji’s traditional role as a regional leader in the Pacific, combined with its experience spearheading both the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) and the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF), places the nation in a strong position to assert its leadership in the region and chart a new path for the future.

As both China and the US continue to increase their influence in the Pacific, the island nations in the region appear to be increasingly faced with the difficult decision of having to choose between the two superpowers. However, Fiji’s foreign policy and its enduring commitment to Pacific regionalism demonstrate that there are indeed pragmatic alternatives to strict alignment with either superpower. Fiji serves as a successful case study of a Pacific Island nation that has managed to strategically navigate increasing geopolitical tensions, and the world will be watching closely as developments in the Pacific region continue to unfold.

Questions

1. Is Pacific regionalism effective in allowing the Pacific Island nations to forge their own path separate from the interests of China and the US?

2. Do you think Fiji is heading towards total realignment with its traditional Western partners, or is this yet another demonstration of Fiji’s flexibility when it comes to its foreign policy?

3. Do you think the US or China is currently “winning” the diplomatic race in the Pacific region? What may be the long-term outcomes?

Suggested readings:

“Fiji Revaluating Ties With China, Main US Indo-Pacific Rival.” VOA News. 7 June 2023.

“Geopolitics in the Pacific Islands: Playing for advantage.” Lowy Institute. 31 January 2024.